By the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, New Orleans was already a music city, offering bals masqués, opera and ballet, military parades with brass bands, choral masses, and virtually nonstop street serenading-all of which coalesced to give birth to jazz. Most people think of New Orleans jazz as a single original jazz idiom, or musical style, when in fact it retains distinctive stylistic features tied to festival traditions within a discrete, regional culture. Even today, the musical practices rooted in neighborhood and family affiliations often influence musical styles and trends among traditional and modern jazz musicians more than national market trends.

In the Antebellum period, weekly “ring shouts” at Place Congo in New Orleans (municipally sanctioned from 1817 to 1856) highlighted the pervasive presence of African and Afro-Caribbean musical sensibilities, also apparent in performances by the black street crier Signor Cornmeal at the St. Charles Theater in 1837, where he alternated with French and Italian opera. Over the course of the nineteenth century in New Orleans, the diversity arising from French, Spanish, and African cultures in the colonial period grew to include European, Caribbean, Latin American, and Asian immigrants, presenting local musicians with a vast array of raw materials from which to draw in making music.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, styles of dance underwent a dramatic shift away from polite, measured, and hierarchical nineteenth-century fare (i.e., quadrille, schottische, waltz, mazurka) to more suggestive, all-purpose steps such as the slow drag, two-step, one-step, and foxtrot, which suited the new musical genres of ragtime, blues, Tin Pan Alley popular tunes, and jazz that were coalescing in the early twentieth century.

Despite the pall of racial segregation instituted by the state legislature in the 1890s and validated by the U.S. Supreme Court with the “separate but equal” doctrine in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, music provided opportunities for people of diverse backgrounds to get together. Much of this activity was made possible by neighborhood settlement patterns that predated segregation. Tremé, the lower French Quarter, and the Seventh Ward (clustered in the downtown area below Canal Street); Central City and the Irish Channel (uptown, above Canal Street); and Algiers (on the West Bank) were all characterized by crazy-quilt settlement patterns, interspersing Creoles, blacks, whites, Jews, Hispanics, and Latinos next door to each other within blocks.

In the period from 1895 to 1925, most jazz musicians came from these neighborhoods, where the outdoor music was taking place. The “hotter” and more expressive dance music that came to be known as jazz catalyzed the attraction of young people. Thus, this musical style, rooted in the good-time practices of the uptown African American community, spread rapidly throughout the metropolitan area, into the rural hinterland, and across the nation.

Traditional New Orleans jazz is band music characterized by a front line usually consisting of cornet (or trumpet), clarinet, and trombone engaging in polyphony with varying degrees of improvisation (without distorting the melody) and driven by a rhythm section consisting of piano (although rarely before 1915), guitar (or, later, banjo), bass (or tuba), and drums delivering syncopated rhythms for dancing (usually, but not always, in common or 4/4 time).

Jazz transformed leadership roles within the older tradition of New Orleans dance bands: In 1900 violinists led the ensemble, but by 1917 their numbers and influence had diminished as volume levels rose and the lead melody role fell to the cornet, then to the trumpet. Within the early jazz ensemble, the clarinet plays obbligato to the lead (primarily with arpeggiated runs), and the trombone engages in various rhythmic pops, growls, and slurs, while also adding harmonic variations and occasionally covering bass lines.

Guitar/banjo and piano reinforce the chord progression and rhythm, while also adding fills during breaks and pickups. The string bass accentuates the first and third beats, sometimes shifting to percussive slap-style eighth-note patterns, especially in the “out chorus,” the final measures of the piece, which were performed with extra energy. The introduction of “trap” drum sets in the 1890s was a major technological leap that enabled intensification and consolidation of rhythmic functions. In a traditional rhythm section, the drummer combines syncopated “press rolls”-even, recurring double-beats, 32 to 64 beats to the measure-and backbeats on snare with ground beats on bass drum. Cymbals are used sparingly, generally for crashes on the upbeat during out choruses or choked accents in stop-time breaks.

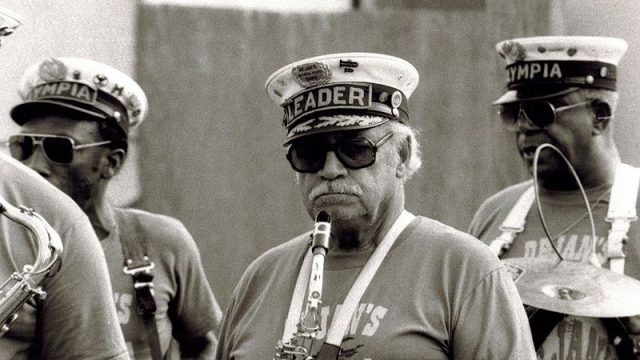

In 1913 the Six and Seven-Eighths String Band of New Orleans engaged in collectively improvised polyphony without brass, reeds, and drums. Gilbert Frank was leader of the Peerless Orchestra in 1905, where he played “hot” piccolo, while his brother Alcide, a violinist, led the Golden Rule Orchestra, which contemporaries characterized as “hotter” than the band led by Buddy Bolden, the first cornet king of jazz. Eventually, saxophones entered the New Orleans front line, as seen in photographs of the Fischbein-Williams Syncopators (1923), Sam Morgan’s Jazz Band (1925), Celestin’s Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra (1928), and the Jones & Collins Astoria Hot Eight (1929). Marching bands that played for second-line dancers in the street, like the Onward Brass Band (a “reading” band that adapted to “faking” around 1905 when jazz became popular) and the Eureka (organized in 1920 as a jazz brass band), usually consisted of ten to 12 instruments: three trumpets, two reeds (originally clarinets; after World War II more likely saxophones), two trombones, brass bass, and snare and bass drummers.

What all these bands shared was a style of playing “hot” dance music that suited the demands of a diverse, music-loving clientele, whether in cabarets, at dance halls, on riverboats, or in the streets. Solo improvisation was not common in New Orleans jazz bands until the mid-1920s, as documented on the recordings of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, Clarence Williams’s Blue Five, and Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five.

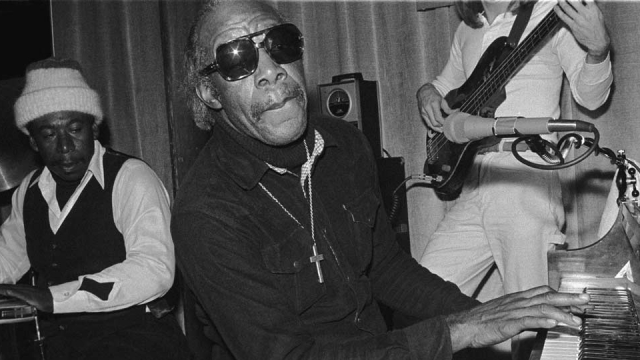

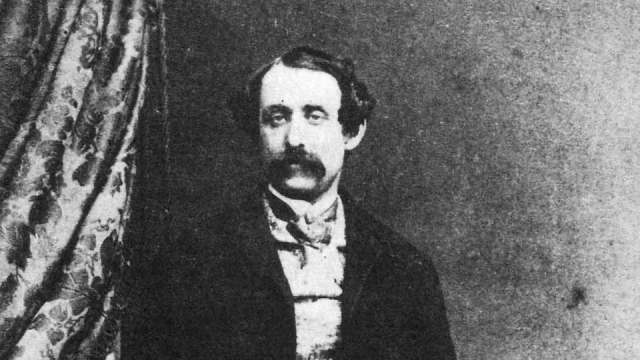

Traditional New Orleans jazz entered the American entertainment mainstream in two ways between 1907 and 1917-through touring and phonograph records. Prior to the first jazz recordings by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in New York in February 1917, New Orleans musicians had already traveled widely throughout North America. For example, the Creole pianist and composer Jelly Roll Morton left the city in 1907 and remained itinerant for most of his life; the Original Creole Orchestra worked the Pantages vaudeville circuit from 1914 to 1918, including Canada; and Tom Brown’s Band from Dixieland played cabarets and theaters in Chicago and New York in 1915.

In 1922, Kid Ory’s Sunshine Band made the first recording by a black New Orleans jazz band in Santa Monica, California, for the obscure Nordskog label. It was the recordings made by New Orleans musicians in the Chicago region from 1923 to 1928 that became the basis for widespread recognition of jazz as an American art form. Continuing the pragmatism that had characterized their musical experiments back home, these musicians employed diverse strategies, while also remaining true to the community cultures on which New Orleans-style jazz was based.

In 1923, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band (featuring Louis Armstrong) relied exclusively on “head” arrangements (tunes worked out in advance and learned by rote) to prepare for its recording sessions, including titles like “Canal Street Blues,” “Snake Rag,” and “New Orleans Stomp.” Beginning in 1925, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five supplemented the occasional use of sheet music with head arrangements and spontaneous ideas generated in the studio to achieve an identifiable sound, leading to recordings like “Heebie Jeebies” (1926), “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue” (1927), and especially “West End Blues” (1928), which were acclaimed as jazz masterpieces.

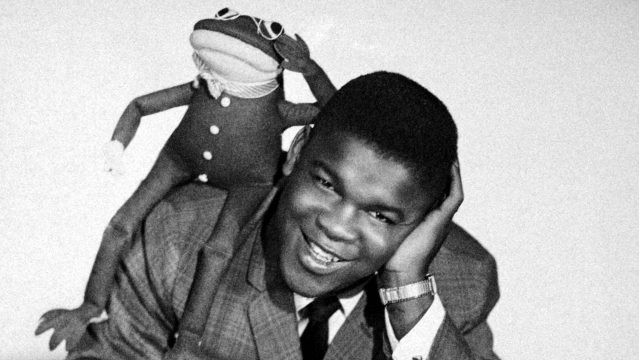

By 1930, the multiplicity of musical possibilities inherent in traditional New Orleans jazz as an idiomatic playing style had amply demonstrated the genre’s potential for open-ended artistic expression. Yet, several coinciding factors spelled the end of the line for traditional New Orleans jazz as a force in the entertainment market: the rise of radio and implosion of the phonograph record boom that had sustained many jazz artists throughout the 1920s; the onset of the Great Depression; and the shifting musical fashion apparent in the rise of big bands whose highly arranged scores left no place for the small-band collective improvisation associated with New Orleans.Only Louis Armstrong continued, fronting a big band that bore little resemblance to the New Orleans-style recording units that had made him famous in the previous decade.

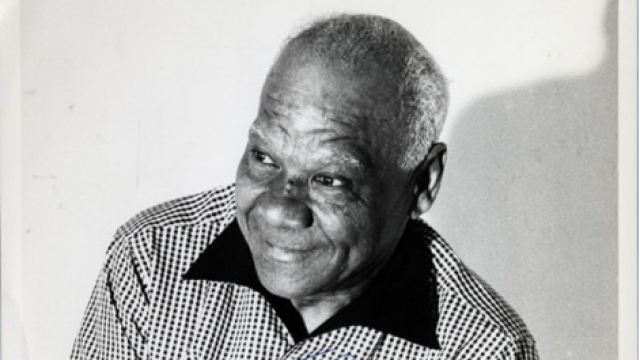

Despite the trends associated with the swing era (represented by clarinetist Benny Goodman’s rise to stardom in 1935), some New Orleans jazz bands persevered and even flourished during the 1930s. Beginning in 1934, New Orleans trumpeter Louis Prima inaugurated a show business career that included jazz, swing combos, big band, Italian ethnic, and rock-and-roll phases, keeping him in the vanguard of American popular entertainment for nearly four decades. Perhaps the most surprising development of all, however, was the “New Orleans Revival” that attended the publication of the early history Jazzmen (1939) by Frederic Ramsey and Charles Edward Smith. This book sparked a highly publicized resurrection of the careers of cornetist Bunk Johnson and trombonist Kid Ory in the 1940s, conceived as an antidote to the rise of bebop and modern jazz in the World War II period. The revival brought previously unknown musicians (particularly the clarinetist George Lewis) to public attention and led directly to the establishment of Preservation Hall in 1961, based on the belief that traditional New Orleans jazz was noncommercial, community-based music that should be protected from the machinations of the music industry.

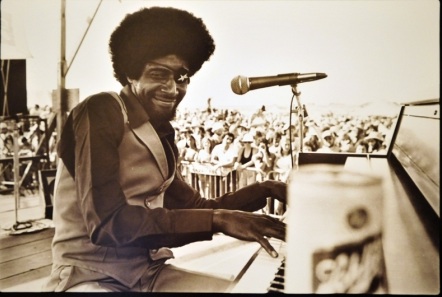

Although New Orleans jazz came very close to extinction during the 1930s, it found ways to survive through experimentation and reinvention. After World War II, a new generation of local musicians interested in modern jazz, including drummers Earl Palmer, Ed Blackwell, and James Black; pianists Ellis Marsalis and Ed Frank; and saxophonists Alvin “Red” Tyler, Nat Perriliat, Harold Battiste, and Edward “Kidd” Jordan, showed that there was room for multiple styles within the New Orleans jazz continuum. This trend continues as the tradition finds new ways to reinvent itself. More recently, the most vital segment of the jazz community has been the new wave of brass bands emerging in the wake of guitarist/banjoist Danny Barker’s Fairview Baptist Church Christian Band experiments in the 1970s, including the Dirty Dozen, the ReBirth, the Hot Eight, and the Pinettes (an all-female group), whose imaginative inclusion of bebop and hip-hop into street repertoire enhances the tradition.