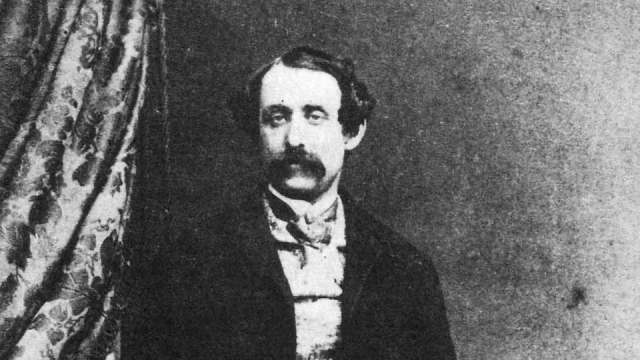

Image Credit: http://thompsonian.info/gottschalk.html

Louis Moreau Gottschalk

1829 – 1869

Image Credit: http://thompsonian.info/gottschalk.html

1829 – 1869

By Ben Sandmel

Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829 – 1869) was the first American classical composer and performer to win international acclaim during an age when many Europeans perceived America as an untamed, uncouth wilderness. Gottschalk rose to Presley-esque levels of stardom, while his prodigious, sophisticated technique garnered praise from such classical masters as Frédéric Chopin.

Gottschalk was a native New Orleanian, and a significant amount of his original material drew on the indigenous Afro-Caribbean and African-American sounds that he heard in the city as a child. One especially notable example is Bamboula, which takes it name from an African-rooted dance that was often performed at slave gatherings at locations in New Orleans such as Congo Square. (The word, “bamboula” refers to a type of drum, originally created in West Africa that was often played at Congo Square.) Gottschalk’s compositions also drew on material by such popular songwriters as Stephen Collins Foster, and additionally incorporated elements of music from Cuba and Puerto Rico, where he traveled extensively as an adult.

Gottschalk stands as one of the first classical composers to utilize American and Caribbean folkloric and popular-music sources, thus paving the way for the likes of Anton Dvorak, Aaron Copland, and George Gershwin. Some experts regard him as a progenitor of early jazz and ragtime.

Gottschalk’s parents realized early on that their son was a child prodigy. When he reached adolescence, they sent him to study in Paris, then the epicenter of classical music training. But in 1841, Gottschalk was summarily turned away from the Paris Conservatory without an audition because, in the dismissive view of the headmaster, “America is only a country of steam engines.” Instead, Gottschalk began taking lessons from Paris’ leading teacher of classical piano, Camille Stamaty. Gottschalk also studied composition with the equally respected Pierre Maledon.

At age sixteen, Gottschalk gave his first public performance, which prompted Chopin – one of the greatest classical piano performers and composers of the day – to shake his hand and state, “I predict that you will become the king of pianists.” This level of acclaim made Gottschalk an in-demand performer in Europe, the United States, the West Indies, and South America. He toured almost continually until approximately 1860, concentrating on original material and sometimes giving three concerts a day.

Today, Gottschalk is praised, by scholars such as Dr. Peter Collins of Missouri State University, for “technical exploitation of the piano, formidable by any standard, [that] set him apart from his contemporaries. Gottschalk’s writing includes interlocking octaves and chords, brilliantly conceived passagework, and complex arpeggio patterns. His unique sonorities run the gamut from percussive bass effects to intricate filigrees in the highest register of the piano. He possessed sound contrapuntal and harmonic capabilities, and a vibrant rhythmic sense influenced by the music of his native Louisiana and surrounding cultures.”

Gottschalk was not universally well received by his contemporaries. An 1853 performance in Boston elicited a chilly response from critic John Sullivan Dwight. Dwight’s Journal of Music was the first substantial American publication to discuss both classical and popular music. Singularly unimpressed with Gottschalk, Dwight wrote, “The extravagant fame and the peculiar kind of enthusiasm which preceded the arrival of the young New Orleans virtuoso, announced in the bills always as ‘the great American pianist,’ had forewarned us what to expect of him. We expected brilliant execution, together with perhaps some little touch of individuality enough to lend a charm to pretty but by no means deeply interesting or important compositions of his own. Some of the compositions we had heard from other players, and by their triviality were forced to feel that either these belied him, or that it was by sheer force of professional puffery that he had so long been proclaimed the peer of… Chopin. …” Dwight went on to praise Gottschalk’s masterful execution, but then added, “…what is execution, without some thought and meaning? … Could a more trivial and insulting string of musical rigmarole have been offered to an audience of earnest music lovers…?”

At the end of the 1850s, Gottschalk cut back on touring and spent several years in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and other Caribbean islands. A significant amount of this time was devoted to absorbing local music, as reflected in such signature compositions as “Souvenir de Porto Rico,” and “Souvenir de la Havane.” After several years on a relaxed schedule, financial concerns compelled Gottschalk to resume touring in 1862, when the Civil War was raging.

Gottschalk always referred to himself as a New Orleanian, and he had strong sentimental and cultural attachments to Louisiana. As Gottschalk biographer S. Frederick Starr explained, the pianist and composer “felt himself to be perpetually in exile from his New Orleans home, an uprooted wanderer in the best Romantic tradition.” Nevertheless, Gottschalk sided with the Northern cause, as expressed in his anthemic composition “Union,” which included excerpts from, and variations on, songs including “The Star Spangled Banner” and “Yankee Doodle.” Gottschalk performed throughout the Union states until 1865, when an alleged impropriety with an underage woman forced him to abruptly decamp to South America. Although Gottschalk’s name was eventually cleared, he never returned to the U.S. In 1869, he collapsed on stage during a concert in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and died shortly thereafter.

Despite the disdain of some critics of his day, Gottschalk’s compositions remained hugely popular after his death – as evidenced by continuing sales of his sheet music. Before the advent of records and radios, such printed scores were comparable to the hit records of future eras. Such sales were enhanced by the fact that, by the latter nineteenth century, many Americans had pianos in their homes. Twenty to twenty-five years after Gottschalk’s death, the music that would come to be known as jazz began making its most important evolutionary steps in New Orleans. At roughly the same time, ragtime evolved, initially in the Midwest, although by the turn of the century it was a national fad.

Based on his penchant for syncopation, the strong Afro-Caribbean influences in his work, and the broad dissemination of his sheet music, Gottschalk has come to be perceived as a major influence on early jazz and ragtime alike; the two genres are, of course, closely related. A turn-of-the-century writer named W. O. Eschwege stated that “ ‘Rag time’ synthesized singularly with [Gottschalk’s] idiosyncrasies as a composer, as is indicated clearly in every bar of his “Pasquinade”… The measures [are] fairly dense with wild constant changes of rhythm which constitute the foundation of what we are pleased to call ‘ragtime,’ probably a contraction of ‘ragged time.’ “

It is theorized that Gottschalk influenced the pioneering New Orleans jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton. Both explored Afro-Caribbean rhythms, as exemplified in Morton’s case by his original composition, “The Crave.” Gottschalk’s popular works were often played in the French-speaking community in New Orleans at the turn of the century, and Morton may well have heard such performances. On a broader note, Morton definitely drew on classical music, among many other sources. In his epic interview in 1938 with Alan Lomax of the Library of Congress, it was noted the songs Morton recorded was a ragtime interpretation of Miserere from Giuseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore.

At this writing, almost one hundred and fifty years after his death, Gottschalk’s work remains revered and influential. In 1992, Dr. John borrowed liberally from “Souvenir de Porto Rico” in writing his song “Litanie des Saints,” the dramatic lead-off track from his Grammy-winning album Going Back To New Orleans. And in 2013, the encyclopedic pianist Tom McDermott released Bamboula. This critically acclaimed album paid tribute to Gottschalk with a reworking of one his songs, along with thirteen McDermott originals that Gottschalk inspired.

——–

_Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based journalist, folklorist, drummer, and producer. Sandmel is the author of Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans and Zydeco!, a collaborative book with photographer Rick Olivier. Sandmel has produced and played on albums including the Grammy-nominated “Deep Water” by the Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers._

Recommended Reading:

Baron, John. H., Concert Life in Nineteenth Century New Orleans (A Comprehensive Reference.) Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

Collins, Peter, Louis Moreau Gottschalk entry from the on-line encyclopedia KnowLouisiana, www.knowlouisiana.org published by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities

Gottschalk, Louis Moreau. Notes of a Pianist: The Chronicles of a New Orleans Music Legend. Edited by Jeanne Behrend. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Loggins, Vernon. Where the Word Ends: The Life of Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1958.

Sablosky, Irving. What They Heard: Music in America, 1852 – 1881, From The Pages Of Dwight’s Journal of Music.

Starr, S. Frederick. Bamboula! The Life and Times of Louis Moreau Gottschalk. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

The piano is a musical instrument played using a keyboard. It is widely used in classical and jazz music for…