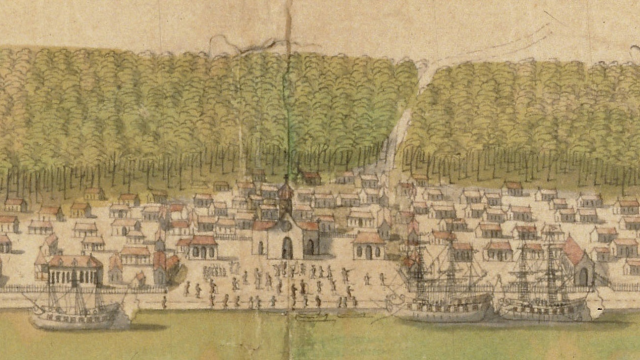

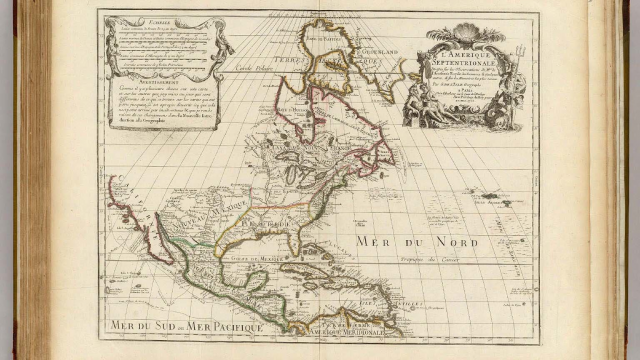

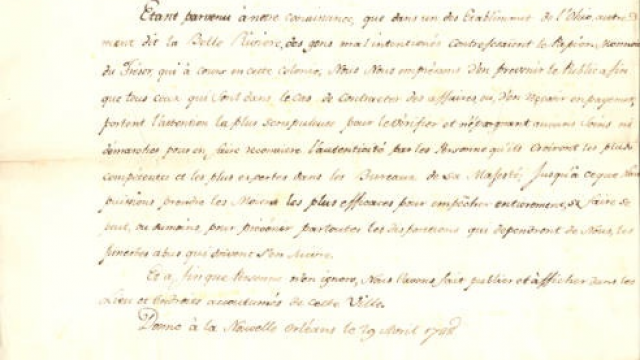

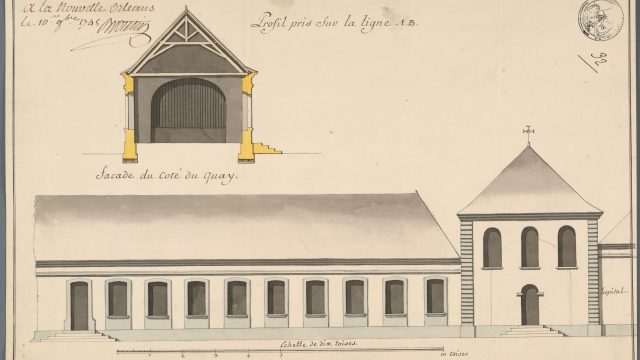

This course explores the connected and comparative histories and cultures of two sites spawned by the Atlantic World phenomena of slave trading and colonization. The Atlantic age lasted from the middle of the 1400s until the early 1800s. The connections between New Orleans and Senegal began in the early 18th century, when thousands of captives were transported from their homeland in Senegambia, today’s Senegal, to become slaves in the French colony of Louisiana. Two thirds of the enslaved men, women and children forced to immigrate to Louisiana during the colony’s French colonial era (1699-1769) came from this region of Africa. Their role in shaping the economy, built environment, and culture of Louisiana and its capital city of New Orleans ensured Senegambia’s permanent imprint on this part of the Gulf South. This early link between the two places was one of many forged over more than two centuries. New Orleans, founded in 1718, was the capital of French colonial Louisiana, and Saint-Louis du Senegal, founded in 1659, was the capital of French colonial Senegal. Both cities perch at the edge of fragile estuarian landscapes and have long relied on the sea for nourishment and economies bound to international trade. Both became canvasses for the projection of European colonial ambitions and ideals at the same time that they gave birth to Creole cultures notable for metissage and hybridity. Both have preserved the architecture of their colonial past, making them popular destinations for tourists seeking the charm and romance of a different era. Both host international jazz festivals, a modern embodiment of musical connections that began when captive Senegambians brought their tradition of plucked gourd instruments to the Americas, where they inspired the evolution of the banjo. Both are associated with exotic, mythologized free women of color, the signares of Saint-Louis and the quadroons of New Orleans.

Back

- African/Caribbean Based Social and Vernacular Dance Forms | DANC 3240-01

- Autobiographies and Southern Identity

- Black Music & Performance in New Orleans | ADST 3550

- Building Community through the Arts | DANC 4900

- Ethnography of Performance and Identity In New Orleans and French Louisiana | ANTH 3395/6395

- French and Creole In Louisiana | FREN 4110/6110

- Gender, Archives, and Musical Culture | GESS 4500

- History of Jazz | MUSC 3340

- Hollywood South | COMM 4810

- Jazz, Blues, and Literature | ENLS 4010

- Languages of Louisiana | ANTH 4930

- Literary New Orleans | ENLS 4030

- New Orleans and Senegal in the Atlantic World | HISU 3100-01

- New Orleans Hip Hop | ADST 1550

- New Orleans Music | MUSC 1900

- The Creation of Jazz in New Orleans | HISU 4694-01

- The Latin Tinge: Jazz and Latin American Music in New Orleans and Beyond | MUSC 3360

- Urban Geography: New Orleans Case Study | AHST3131