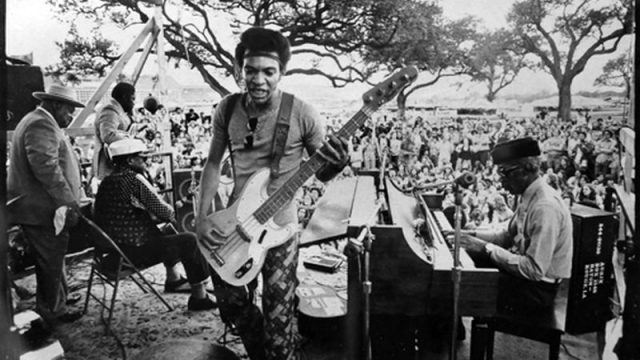

Image Credit: Michael P Smith

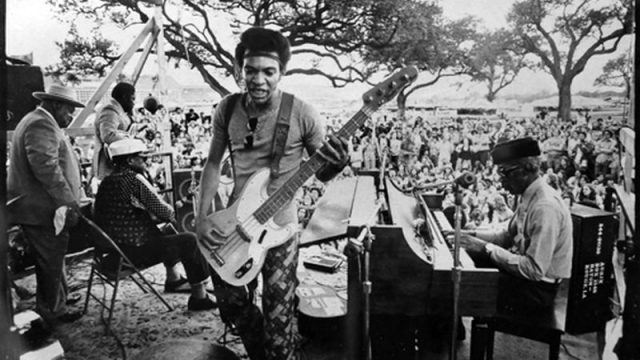

Image Credit: Michael P Smith

Few words conjure as many meanings and ideas as the word funk. It is a type of music, a way of playing music, a rhythm, a scent, a description, a concept, a philosophy, and an entire way of life. It has been used to portray and describe everything from food to music to style to neighborhood ambience. The meaning of funk translates only in context: it has subtle and infinite variations depending on how the word is used and where. The main concern here is the genre of funk music, yet and still, any understanding of the music must include a discussion of the origins of the term

Funk or funky in a general sense means soiled, carnal, dirty or possessing a strong smell, but its positive connotations concern earthiness, sex, and sweat. In Flash Of The Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy, the anthropologist Robert Farris Thompson traced the origins of the word to the language of the Kongo civilization of Africa (today, the Congo and Gabon): “lu-fuki” meant “bad body odor.” For the Kongo, signs of exertion are identified with the positive energy of a person. For instance, the smell of a hardworking elder in the Kongo culture is good luck.

Both “funky” and “lu-fuki” have always been used as words of praise for individuals and the integrity of their art. If one has “worked out to achieve their goals” and exerted themselves to accomplish their aims, they are complimented by being called “funky.” Thompson theorized that “lu-fuki” might have combined with the French Louisiana word “fumet,” referring “the aroma of food and wine.”

The concept of funk survived the Middle Passage and the experience of slavery to create a positive identification with the odors of sex and the body. It is unknown when funk began to refer to music, but as early as 1907, the primogenitor of jazz, cornet player Charles “Buddy” Bolden was known for a song called “Funky Butt.” Jelly Roll Morton rewrote the original composition (lost to history) as “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say” and it included these lyrics: “I thought I hear Buddy Bolden say/stinky butt, funky butt, take it away/I thought I heard Buddy Bolden shout/open up the window and let that bad air out.” Morton’s relaxed playing on this composition shows how music described as funky was slow, sexy, loose, and easy to dance to. In essence, funk refers to – and values – primal experience.

New Orleans was a major site for locating funk as it evolved from referring to embodied qualities of music – e.g., “that was funky” — to a musical genre itself. Professor Longhair, born Henry Roland Byrd, lived in the neighborhood of Central City and described many of the barrelhouse and dive bars where he played as “funky.” Longhair took the boogie-woogie style of the 1920s and 1930s, and added a triplet with a rhumba beat to the left hand. In short, as Tad Jones suggests, he “superimpose[ed] very fast triplets over a syncopated 8/8 rumba beat.” Longhair also augmented this by kicking the piano with his foot, often with such force that he kicked holes in the bases of upright pianos.

Earl Palmer was the drummer on many of the early rhythm and blues hits that came to define the kind of New Orleans rock-and-roll that led to early funk in the work of Fats Domino, Little Richard, and others. Palmer developed a funk rhythm on these records by imitating the street beats of second-line parade bands. He would mix the syncopation of two separate drummers, the bass drummer and the snare drummer, on one drum kit. In ‘Funky Drummer’: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music, Alexander Stewart credits Palmer with hitting the bass drum on the downbeats and the hi-hat on the upbeats. That was the foundation of funk. Then Palmer funked it up by playing straight eighth-notes while implying sixteenth-note triples on songs like Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin'” and Little Richard’s “Keep A-Knockin.'” When Palmer exhorted his fellow musicians to make the music “funkier” and “stankier,” he was referring musically to this rhythmic combination of repeated eighth and sixteenth notes.=

As funk developed further in other cities, New Orleans remained an important musical satellite of the genre. Drummers in New Orleans such as Charles “Hungry” Williams, Joseph “Smokey” Johnson, Idris Muhammad, and Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste updated Palmer’s beats as derived from street parades. When James Brown shifted from a soul feel to a funk groove, his drummer was Clayton Fillyau, a man who, early in his career, rehearsed with the iconic New Orleans band, Huey Piano Smith and the Clowns when they toured Florida in the 1950s. Fillyau’s funk groove on Live At the Apollo (1962) and singles such as “I Got Money” set the national stage for funk drumming. In addition, future James Brown drummer Jabbo Starks picked up on funk drumming from listening to New Orleanian Tennoo Coleman, Fats Domino’s touring drummer.

James Brown and his Famous Flames developed the complexity of funk in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Brown changed the downbeat to the first beat of every measure, as you can hear on his live recordings when he exhorts the crowd (or his band), “It’s all on the one.” Instruments syncopated and played off-beats around the first beat. Each instrument had a specific – and sometimes very simple – part, but when put together with all the other parts, there was a dense, interlocking rhythmic foundation. Brown sacrificed harmonic development to rhythmic complexity, a musical decision that eventually led to hiphop. In the 1970s, younger bands such as Parliament/Funkadelic, Sly and the Family Stone, and The Ohio Players extended Brown’s innovations with extended song structures, humorous and profane lyrics (and attitudes), and even Afrofuturism.

Funk has also been a regional music. There was New York’s slick, sophisticated funk, Detroit’s loose, psychedelic funk, and the dance-party Latino funk of Los Angeles. New Orleans funk also had its own sound based on The Meters, the city’s most famous and influential funk band. The Meters played a stripped-down, minimalist funk, as worked out by four musicians: Art Neville – organ; George Porter Jr. – bass; Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste – drums; and Leo Nocentelli- guitar. Following the model of James Brown, The Meters created a deep, interlocking groove while soloists darted in and out. The band’s biggest hit, “Cissy Strut,” peaked at #4 on the Billboard Rhythm-and-Blues chart in 1969, kicking off a five-year creative period that culminated with their best album, Rejuvenation (1974). Another key figure in New Orleans funk was Mac Rebbenback aka Dr. John. He was originally a session musician (and guitarist) in New Orleans. When he moved to Los Angeles, Rebbenback teamed up with fellow expat New Orleanian Harold Battiste and they created the character of Dr. John, a figure based on a 19th-century New Orleans voodoo priest. Dr. John added a swamp, psychedelic sound and a growling voice to the piano riffs of Professor Longhair, his most important influence on piano. His biggest hit was “Right Place Wrong Time” (1973) and reached the Billboard Top 20.

The Meters broke up in 1978. Art Neville and his brother Cyril (percussion) to joined their brothers, Aaron (on vocals) and Charles (saxophone) to form The Neville Brothers. The Nevilles became renowned for their funky live shows, adding layers of Caribbean percussion to the New Orleans mix. The band played together until the rupture of Hurricane Katrina scattered the family. The Nevilles influenced a shift in brass-band funk – away from spirituals and standards and towards more popular music (and party music) at parades, clubs, and parties.

A funk revival hit Louisiana and New Orleans in the 1990s. Bands such as All That and Iris May Tango enjoyed some regional success, but it was Galactic that created a new local funk sound. This five piece band has evolved from a college jam band to the funk groove of The Meters to working with hip-hop DJs and rappers in reflecting the complex local music scene. To Mardi Gras record that explores the different types of Carnival music. New Orleans has one other premier funk band, Dumpstaphunk. Led by keyboardist Ivan Neville (Aaron’s son), it features Ian Neville (Art’s son) and two bassists, Nick Daniels and Tony Hall, both of whom started out playing in the Neville Brothers’ rhythm section.

Funk continues to be a potent musical force — in Louisiana, in the Gulf South, and in global culture. It is a genre that yokes together emotional highs (in its vocals) with low-down earthiness (rhythm section). This is a core African-American cultural practice: signifying on a seemingly negative term (the word “bad”) and inflecting it in a positive manner. Funk is a concept and a musical genre grounded in New Orleans origins and the city continues to shape its future.

For Further Reading:

Berry, Jason, John Foose, and Tad Jones. Up from the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II. Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2009.

Bolden, Tony, editor. The Funk Era and Beyond: New Perspectives on Black Popular Culture. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008.

Payne, Jim. Give The Drummer Some: The Great Drummers of R&B, Funk, and Soul. New York: Manhattan Music, 1996.

Rapani, Richard J.. The New Blues Music: Changes in Rhythm and Blues 1950 – 1999. Oxford, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2006.

Stewart, Alexander. ‘Funky Drummer’: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: Popular Music, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Oct., 2000), pp. 293-318.

David Kunian is a New Orleans-based music writer and DJ on WWOZ-FM.