By Ben Sandmel

The Cajun music of southwestern Louisiana and east Texas shines as one of America’s most significant and distinctive indigenous genres. Currently in the fourth decade of a rich cultural renaissance, Cajun music is most frequently performed today by bands in which the diatonic accordion is the dominant signature instrument. Fiddles, acoustic and/or electric guitars – and in some cases, steel guitars – provide accompaniment and contribute solos alike, and most bands are anchored by a rhythm section of an electric bass and a full drum kit. This familiar sound and visual image belie the fact that, during approximately 250 years of existence, Cajun music has undergone significant changes in terms of instrumentation and repertoire.

The term “Cajun” is a shortened form of “Acadian.” The Acadians were residents of Acadie, a prosperous French colony in what is now Nova Scotia, in eastern Canada. They had emigrated to Canada from western France, with two rich musical traditions in tow: fiddle music, and a capella ballads. Some of this music had clearly discernible medieval roots. The fiddle repertoire was primarily played to accompany dancing and included such song forms as waltzes, reels, contre-danses, jigs, mazurkas, and schottisches. The a capella ballads ranged from centuries-old historic narratives to children’s play songs and lullabies, and were sung more often by women than by men.

Britain took control of Acadie in 1713 and deported the Acadians in 1755. A significant number of Acadian exiles eventually settled in south Louisiana on the west side of the Atchafalaya Basin. Their rural, agrarian communities were quite separate from the urbane world of French New Orleans, and remained physically and culturally isolated until the early 20th century. Such separation nurtured the survival of Acadian music, but not to a monolithic extent. Cajun musicians interacted significantly with Africans, and several generations later, African-Americans, as well as Afro-Caribbean Creoles who came to southwest Louisiana from Haiti. In the mid-twentieth century these people’s French-speaking descendents would go on to create Cajun music’s Creole counterpart, zydeco. Louisiana’s status as a Spanish colony during the late eighteenth century left its imprint upon Cajun music as well, as did the musical traditions of local Native American tribes. Then, during the latter nineteenth century, German and Austrian peddlers brought the recently invented accordion to Louisiana. It caught on quickly, in that pre-electrified era, as the only instrument that could cut through the noise of a crowd at a dance, and has served as a symbol of Cajun music ever since.

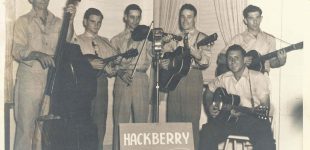

The advent of the recording industry in the 1920s coincidentally documented the folkloric Cajun music of the day, which had yet to become commercially self-conscious, although such canny awareness would follow soon. At this time, Cajun music was dominated by accordion and fiddles playing two-steps and waltzes for dancers. The first such record in this mode, “Allons A Lafayette” by accordionist Joseph Falcon, (with guitar accompaniment by his wife, Cleoma), appeared in 1928. During the 1930s the accordion went out of vogue, temporarily, during an era of string-band dominance typified by the Hackberry Ramblers. The 1930s also saw the deliberate, extensive documentation of folkloric Cajun and Creole music thanks John and Alan Lomax’s crucially important fieldwork, conducted for the Library of Congress. Much of what we know today of Cajun and Creole music history is based upon these recordings.

The accordion returned to prominence after World War II, led in large part by Iry LeJeune, and Nathan Abshire. By this time many Cajun bands featured amplified instruments and were driven by bass and drums. Continuing a trend that had started in the ‘30s, Cajun music increasingly interacted with Anglo-American country music. This created the mistaken impression within mainstream culture that Cajun music was simply country music, sung in French. To cite one example, this notion is disproved by the fact that Hank Williams’ hit “Jambalaya” made note-for-note use of the melody to a Cajun song known as both “L’anse couche-couche” and “Grand Texas.”

By the 1960s, a time of great pressure for cultural assimilation, Cajun music reached a low ebb of popularity and seemed threatened with extinction. Fiddler Dewey Balfa carried the torch of cultural conservation during this difficult era, and brought Cajun music its first national exposure by performing at the prestigious Newport Folk Festival. In the 1970s, however, a fresh breeze of cultural pride and appreciation created unprecedented resurgence in the popularity of Cajun/Creole music and culture. Musicians such as Zachary Richard and Michael Doucet helped spearhead this movement, as did folklorist Barry Ancelet. Richard and Doucet – the latter via his band BeauSoleil – combined reverence for tradition with forward-thinking eclecticism by reviving archaic songs while also incorporating elements of contemporary rock and jazz. A decade later, Cajun music became positively trendy for several years, in with a fascination for Cajun cuisine. Second-generation culture warriors such as Wayne Toups and Steve Riley emerged at this time to advance Cajun music’s cutting edge.

At this writing, the past quarter-century has seen Cajun music continue to flourish, from the ground up on the grassroots, community level. Young bands including FeuFollet, the Lost Bayou Ramblers, and the Pine Leaf Boys reprise the duality of traditionalism and modernism first explored by Zachary Richard and Michael Doucet, and they perform this mixture for worldwide audiences. Artists such as Jambalaya, Ray Abshire, Robert Jardell, Belton Richard, D. L. Menard, and the Lafayette Rhythm Devils, among others, create subtle variations on the traditional, somewhat more conservative Cajun repertoire that is popular on the south Louisiana dancehall circuit where they perform. Wayne Toups plays this circuit while also touching on southern rock for other audiences. The Savoy Family Band, Jesse Lege, and Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys take their traditional yet eclectic sound around the world. Women, important conservators of the home-based ballad tradition – which is still performed by such dedicated singer/researchers as Marce Lacouture – now work the local and global touring circuits in all-female groups such as Bonsoir Catin, and the Magnolia Sisters. And the full, comprehensive range of this vibrant scene is presented annually at Festivals Acadien et Creole, in Lafayette.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based journalist, folklorist, drummer, and producer. Sandmel is the author of Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans and Zydeco!, a collaborative book with photographer Rick Olivier. Sandmel has produced and played on albums including the Grammy-nominated “Deep Water” by the Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers.

Suggested Reading:

Ancelet, Barry Jean and Morgan, Elemore, Jr. Cajun and Creole Music Makers: Musiciens cadiens et creoles. Jackson, MS. The University Press of Mississippi, 1999

Ancelet, Barry Jean. “Cajun Music,” a chapter in the anthology Accordions, Fiddles, Two-Steps and Swing: A Cajun Music Reader, pp 197 – 227. Lafayette, Louisiana. The University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2006

Ancelet, Barry Jean, Cajun Music: Its Origins and Development. Lafayette, LA. The University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 1989.