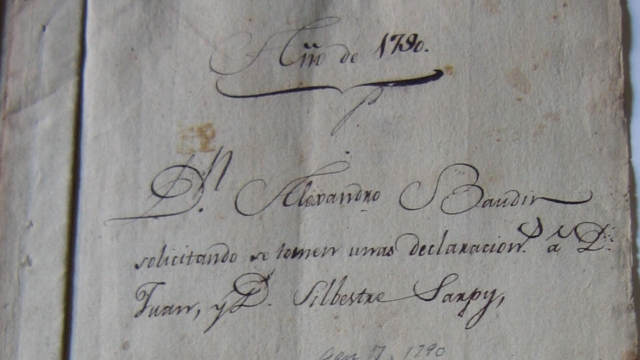

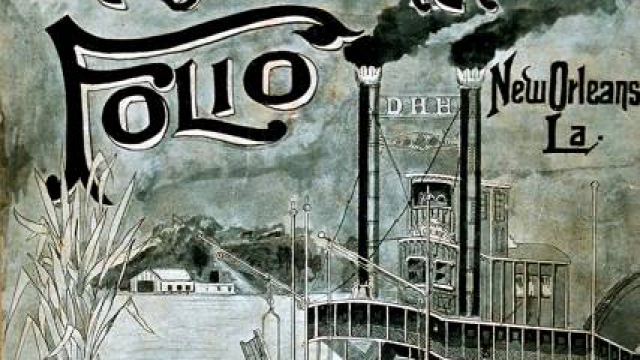

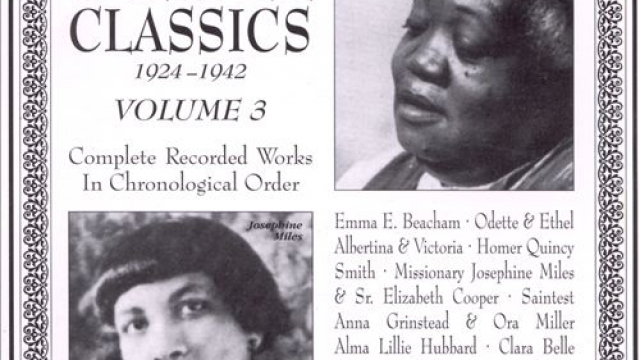

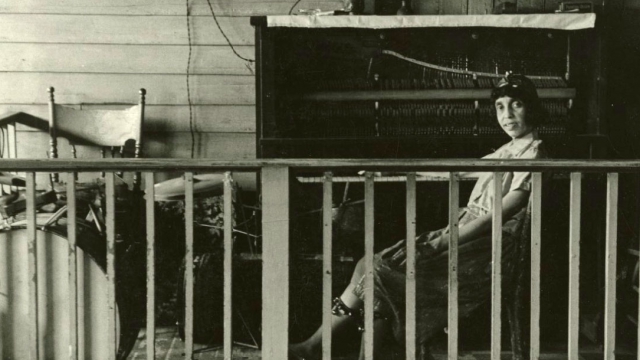

The Gulf South is a region rich in records and manuscripts upon which scholars base their work. Here, one can find inheritances of Spanish and French colonial records; Catholic registries of birth, marriages, and deaths; and a notarial culture that gave precise notices of transfers of property, wills, marriage contracts, and other declarations. How is music found in these written and visual riches? And are women and men musicians represented differently in these tangible steppingstones to the past? This course explores these questions through biographical and subject inquiries. In visits to local archives, work in these archives, class readings, and audio and visual examples, the class is introduced to particular cultures of archives, gender, and music. The chapters here give a sampling of this work.

Back

- African/Caribbean Based Social and Vernacular Dance Forms | DANC 3240-01

- Autobiographies and Southern Identity

- Black Music & Performance in New Orleans | ADST 3550

- Building Community through the Arts | DANC 4900

- Ethnography of Performance and Identity In New Orleans and French Louisiana | ANTH 3395/6395

- French and Creole In Louisiana | FREN 4110/6110

- Gender, Archives, and Musical Culture | GESS 4500

- History of Jazz | MUSC 3340

- Hollywood South | COMM 4810

- Jazz, Blues, and Literature | ENLS 4010

- Languages of Louisiana | ANTH 4930

- Literary New Orleans | ENLS 4030

- New Orleans and Senegal in the Atlantic World | HISU 3100-01

- New Orleans Hip Hop | ADST 1550

- New Orleans Music | MUSC 1900

- The Creation of Jazz in New Orleans | HISU 4694-01

- The Latin Tinge: Jazz and Latin American Music in New Orleans and Beyond | MUSC 3360

- Urban Geography: New Orleans Case Study | AHST3131