By Ben Sandmel

Rhythm & blues – also known as R&B – is an African-American commercial music genre with distinct roots in traditional blues and gospel music. While significantly influenced by such sources, R&B also differs in that those songs are written with the deliberate goal of crafting a hit.

Blues and gospel artists also seek success, but many traditional blues and gospel songs draw on a vast body of folk-rooted lyrics, known as collectively floating verses, which appear in many songs – different combinations that are sometimes random and thus can be thematically vague. The aggressive market-driven orientation of R&B manifests in its penchant for lyrics that tell succinct stories and the prominent inclusion of brief, catchy and instantly identifiable passages – vocal, instrumental or both – that are known in the record business as “hooks.” The presence of memorable hooks – in songs of any commercial genre – dramatically increases the chances for that song’s commercial success. Ernie K-Doe’s R&B hit, “Mother-In-Law” offers a prime example of a song that combined a strong hook – its title phrase – with a pithy narrative to reach number-one on the national pop and R&B charts.

R&B evolved in the 1940s as a convergent hybrid of several genres. Traditional blues contributed such bedrock African-American musical traits as call and response, melisma, syncopation, improvisation, and the prominent use of blue notes – the flatted third, fifth, and seventh in any given scale. R&B diverged from traditional blues songs by expanding beyond the typical blues song-structure – twelve bars, an A-A-B verse pattern, and a one-four-five chord progression – to use widely varying chord progressions and often, distinct and unique melodies. Similarly drawing on tradition, while straddling the secular/sacred boundary, R&B utilized gospel music’s sophisticated tradition of quartet singing, which maximized the dramatic contrast between the four alternating vocal leads. Early R&B also reflected the influence of various jazz styles – the classic New Orleans sound of Louis Armstrong, Jelly Morton, and Sidney Bechet; the humorous, virtuosic records of the great pianist, singer and composer Fats Waller; big-band swing a la Count Basie; the boogie-woogie craze of the ‘30s and ‘40s, and a style known as jump-blues that combined elements of all of the above. One of the most popular exponents of this latter sound was Louis Jordan and the Tympani Five – a band that is sometimes regarded as a proto-R&B group, thus underscoring the arbitrary and at times confusing nature of precise musical categorization. In south Louisiana, R&B additionally absorbed the Afro-Cuban three-count tresillo rhythms that reflect the region’s strong connections with Caribbean culture, as well as the second-line street beats of the traditional-jazz brass bands.

While rhythm & blues was a national trend, many of its most important developments occurred in south Louisiana – most notably in New Orleans, but also typified by the “swamp blues” sound of Baton Rouge, exemplified by Slim Harpo, and the Cajun-zydeco infused “swamp pop” of Lafayette/Opelousas/Lake Charles, exemplified by Bobby Charles, Phil Phillips and Carol Fran. The common thread in all three south Louisiana styles was an infectious, rowdy exuberance on up-tempo numbers, and soul-baring poignancy on the slow songs.

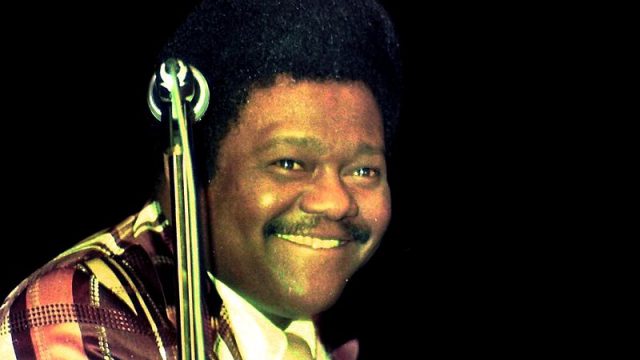

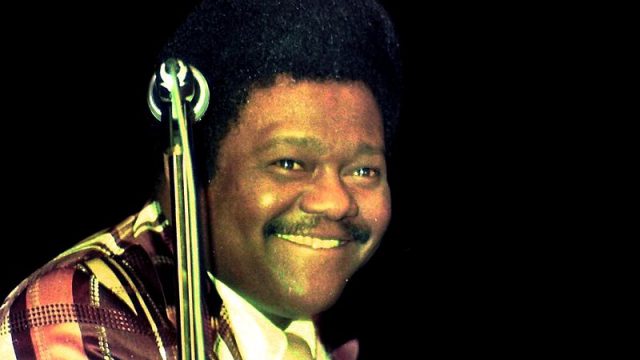

Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” which climbed the R&B charts in 1948, was the first hit in this genre to be recorded in New Orleans. Its national success was followed by such hits as Fats Domino’s “The Fat Man” in 1950, Lloyd Price’s “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” in 1952, and Guitar Slim’s “The Things I Used To Do” in 1954. The success of these artists and others prompted record companies based around the nation to send their A-list artists to New Orleans to work with the city’s stellar studio musicians and its best audio engineer, Cosimo Matassa. Record labels including Atlantic, Imperial, Specialty and Chess could easily have worked at less expense in the major cities where they were based, but they opted for New Orleans, where Matassa and his cadre of session players were thought to possess that certain intangible feel which guaranteed commercial success. These record executives’ collective hunch proved right on hits such as Big Joe Turner’s “Honey, Hush” and Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally.”

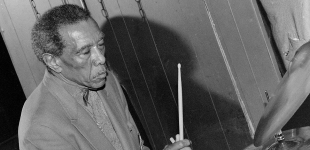

A vast surge of creativity and commercial success energized the Crescent City from the late 1940s to the early 1960s, an era later dubbed the Golden Age of New Orleans rhythm and blues. A cursory list of its other luminaries includes Professor Longhair, Shirley and Lee, Smiley Lewis, Irma Thomas, James Booker, Lee Dorsey, Art Neville, Aaron Neville, Huey “Piano” Smith, Frankie Ford, Clarence “Frogman” Henry. The Meters and Dr. John, who emerged in the late 1960s, and the Neville Brothers (with siblings Aaron, Art, Charles, and Cyril), who formed a decade later, also stand in that illustrious number. So do the musicians who accompanied these artists on many of their records: saxophonists Lee Allen and Nat Perrilliat, drummers Earl Palmer and Smokey Johnson, bassists Frank Fields and Lloyd Lambert, and guitarists Roy Montrell, Justin Adams and “Deacon” John Moore, to name but a few.

While The Golden Age eventually gave way to the British Invasion and other trends that followed, New Orleans R&B remains vibrant and popular. At this writing, such seminal artists as Aaron Neville, Allen Toussaint and Irma Thomas continue to enjoy active careers in undiminished peak form, while comparatively younger musicians including Davell Crawford carry the Crescent City torch. Baton Rouge artists Chris Thomas King and Larry Garner expertly honor that city’s blues-drenched R&B legacy, while swamp pop flourishes thanks to such thriving originators as Warren Storm, T. K. Hulin, Carol Fran and Tommy McLain, the multi-generational Lil’ Band ‘o’ Gold, and the second-generation Creole String Beans.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based journalist, folklorist, drummer, and producer. Sandmel is the author of Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans and Zydeco!, a collaborative book with photographer Rick Olivier. Sandmel has produced and played on albums including the Grammy-nominated “Deep Water” by the Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers.

Suggested Reading:

Bernard, Shane K., Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues. Jackson, MS. The University Press of Mississippi. 1996

Berry, Jason, Foose, Jonathan, and Jones, Tad. Up From the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II. Lafayette, LA. The University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. 2009.

Broven, John. South To Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous. Gretna, Louisiana. Pelican Publishing, 1983.

Broven, John. Rhythm & Blues In New Orleans. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1988.

Coleman, Rick. Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock ‘n’ Roll. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2006.

Dr. John (Mac Rebennack), with Rummel, Jack, Under A Hoodoo Moon: The Life of the Nite Tripper. New York, Saint Martin’s Press, 2004.

Hannusch, Jeff. I Hear You Knockin’: The Sound of New Orleans Rhythm & Blue. Ville Platte, LA: Swallow Publications, Inc., 1985.

Hannusch, Jeff. The Soul of New Orleans. A Legacy of Rhythm and Blues. Ville Platte, LA, 2001. Swallow Publications, 2001.

Sandmel, Ben. Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans. New Orleans, the Historic New Orleans Collection. 2012.