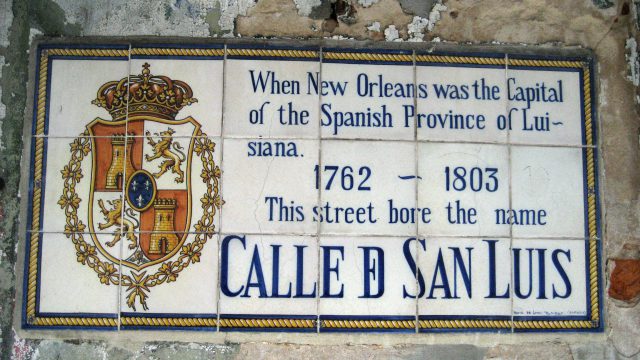

This course examines the current and historically diverse linguistic situation in Louisiana, from indigenous languages spoken at the time of contact with Europeans to the present, in particular on the colonial languages that influenced the English spoken today. It covers basic features of the languages as well as their social settings. Students will further conduct independent field research projects, alone or in small groups, focusing on languages spoken in southern Louisiana, in particular in the city of New Orleans.

Back

- African/Caribbean Based Social and Vernacular Dance Forms | DANC 3240-01

- Autobiographies and Southern Identity

- Black Music & Performance in New Orleans | ADST 3550

- Building Community through the Arts | DANC 4900

- Ethnography of Performance and Identity In New Orleans and French Louisiana | ANTH 3395/6395

- French and Creole In Louisiana | FREN 4110/6110

- Gender, Archives, and Musical Culture | GESS 4500

- History of Jazz | MUSC 3340

- Hollywood South | COMM 4810

- Jazz, Blues, and Literature | ENLS 4010

- Languages of Louisiana | ANTH 4930

- Literary New Orleans | ENLS 4030

- New Orleans and Senegal in the Atlantic World | HISU 3100-01

- New Orleans Hip Hop | ADST 1550

- New Orleans Music | MUSC 1900

- The Creation of Jazz in New Orleans | HISU 4694-01

- The Latin Tinge: Jazz and Latin American Music in New Orleans and Beyond | MUSC 3360

- Urban Geography: New Orleans Case Study | AHST3131