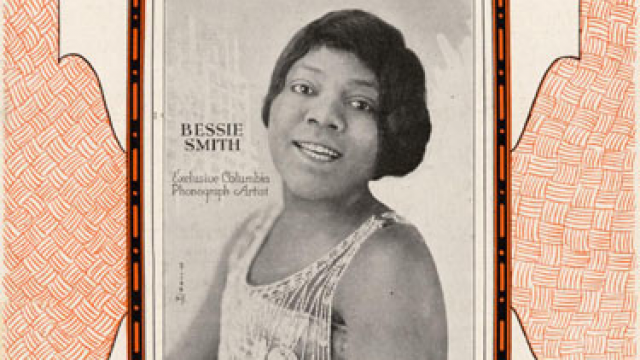

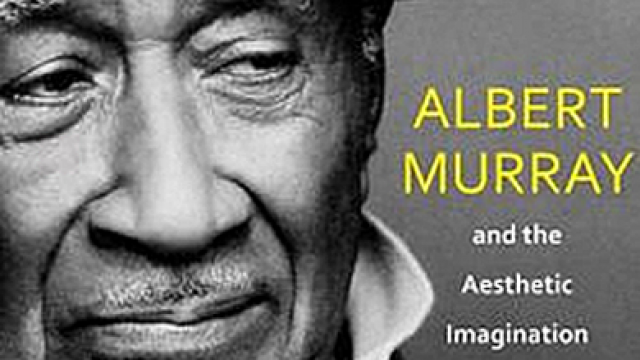

As forms of artistic expression, jazz, blues and literature challenge each reader and listener to consider everyday life as an improvisational challenge. Authors and musicians model for readers and listeners a path for finding one’s voice, for speaking out within a community and for expressing one’s experience from a distinctly personal (or subjective) perspective. Literary theorist Kenneth Burke called the reading of literature “equipment for living” and blues theorist Albert Murray adapted this phrase for African-American music. Burke and Murray both intended the same meaning concerning the aesthetic objectives of art: that if readers (of literature) or listeners (of blues or jazz) internalize the messages within these art forms, they will increase their level of self-understanding. “Jazz, Blues and Literature” integrates music, literature, history, race and ethnicity, aesthetics and local traditions — in other words, this course analyzes the relationship of music and place, of site and sound. We begin at the beginning by exploring the conditions under which jazz and blues arose at the turn of the twentieth century in New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta.

Back

- African/Caribbean Based Social and Vernacular Dance Forms | DANC 3240-01

- Autobiographies and Southern Identity

- Black Music & Performance in New Orleans | ADST 3550

- Building Community through the Arts | DANC 4900

- Ethnography of Performance and Identity In New Orleans and French Louisiana | ANTH 3395/6395

- French and Creole In Louisiana | FREN 4110/6110

- Gender, Archives, and Musical Culture | GESS 4500

- History of Jazz | MUSC 3340

- Hollywood South | COMM 4810

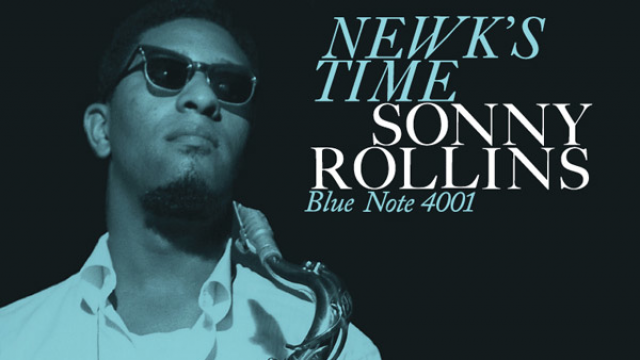

- Jazz, Blues, and Literature | ENLS 4010

- Languages of Louisiana | ANTH 4930

- Literary New Orleans | ENLS 4030

- New Orleans and Senegal in the Atlantic World | HISU 3100-01

- New Orleans Hip Hop | ADST 1550

- New Orleans Music | MUSC 1900

- The Creation of Jazz in New Orleans | HISU 4694-01

- The Latin Tinge: Jazz and Latin American Music in New Orleans and Beyond | MUSC 3360

- Urban Geography: New Orleans Case Study | AHST3131