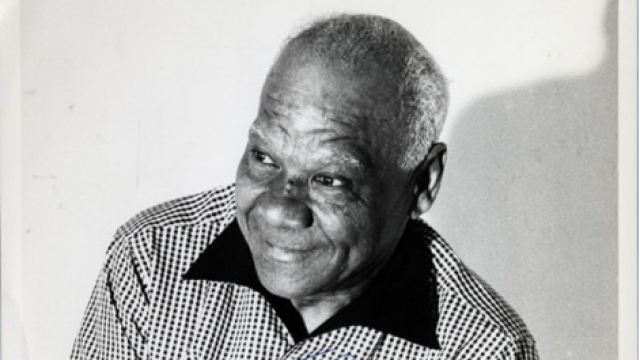

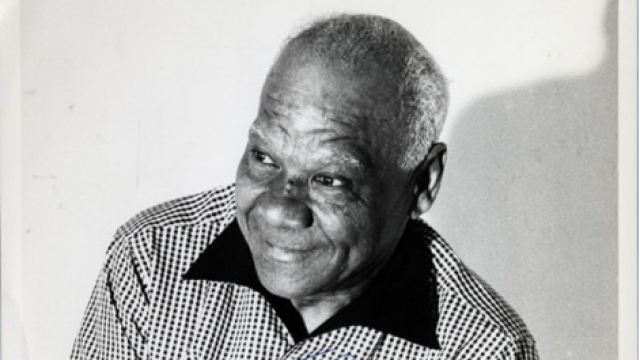

Sidney Bechet

1897 – 1959

1897 – 1959

By Ben Sandmel

Alongside such greats as Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, clarinetist/soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet stands out as a premier soloist of traditional New Orleans jazz. Bechet continues to exert considerable, multi-generational influence on the traditional jazz scene both in New Orleans and worldwide – especially in his late-in-life home of France. He is acclaimed for his lyrical phrasing, bluesy sensibility, idiosyncratic use of vibrato, and ineffable sense of swing.

Bechet’s middle-class black Creole family far preferred mainstream European music (which was very popular in early nineteenth-century New Orleans) to the African-Caribbean sounds that were then blending with European notation and instrumentation to evolve into jazz. Many in New Orleans’ black Creole community disliked jazz, deeming it low-class and reinforcing that concept by disdainfully calling it “ratty” music. As Sidney Bechet’s brother Leonard once explained, “Us Creole musicians always did hold up a nice prestige.” Despite this view of jazz, Bechet’s family encouraged him to develop the innate talent that he had clearly demonstrated while still a young child. This became obvious when the great jazz cornetist Freddy Keppard and his band performed at a party at the Bechet’s home when Sidney was ten years old. Keppard’s group included a respected clarinetist named George Baquet, who came late to the party. His absence was not noted, however, because young Sidney played along from another room, to the ultimate surprise of all who assumed they were listening to Baquet. Soon Bechet became Baquet’s student. He also studied with clarinetists Lorenzo Tio, Jr. and Louis “Big Eye” Nelson (DeLille.) Despite Bechet’s great interest in learning, he did not care for formal training, preferring instead to improvise.

In his teen years Sidney Bechet first appeared in public as a member of the Silver Bell Band, which was led by his brothers. Next he joined the Young Olympians, a venerable outfit that is still active at this writing, and then moved on, yet again, to play with cornetist Bunk Johnson in the Eagle Band, a group once led by Buddy Bolden. Soon Bechet was working with Clarence Williams, a Louisiana pianist/composer/entrepreneur whose work encompassed blues, ragtime, early jazz, and show tunes. Williams took the teenaged Bechet on the road, which eventually led to a tour of Europe, in 1919, with violinist and ragtime composer Will Marion Cook. Bechet’s masterful, articulate improvisations were praised by the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet, who called him “an extraordinary clarinet virtuoso” and praised his “extremely difficult” solos for their “richness of invention, force of accent, and daring in their novelty and the unexpected.” This was a remarkable endorsement at a time when jazz was largely scorned in classical music circles.

Bechet returned to America and, in 1923, recorded with Clarence Williams’ Blue Five, a band that, on a 1924 session, also included Louis Armstrong. During this same period, Bechet also worked briefly with Duke Ellington’s orchestra. He then went back to Europe, building a reputation as an accomplished musician with a wild personality. Jailed in Paris after a shooting incident, Bechet was deported from France in 1929. He went to Berlin, and appeared in the musical film Einbrecher. Returning to the U.S., Bechet began working with bandleader Noble Sissle, of Shuffling Along fame, in 1930.

During the ‘30s, Bechet primarily based himself in New York. Joining forces with another hometown expatriate, trumpeter Tommy Ladnier, Bechet formed a band called The New Orleans Feet-Warmers. This group’s recordings included “Shake It and Break It” and “Shag.” Bechet and Ladnier also worked, for a time, in Noble Sissle’s orchestra. In addition, the two also set up a tailoring business to supplement their between-gigs income.

Bechet’s interpretation of “Summertime” brought him considerable attention in 1938. Three years later 1941, he participated in one of the first over-dubbed recordings when he played the clarinet, soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone, piano, bass, and drums on a rendition of “The Sheik of Arabi.” When a traditional New Orleans jazz revival took off in the late ‘40s, particularly in Europe, Bechet returned to France. With his 1929 deportation regarded as an old and now-resolved problem, Bechet toured France with increasing frequency, welcomed as a cultural hero. This warm reception spurred Bechet to move to France in the early ‘50s. His best-known song from this era was a reworking of the old Creole song “Les Oignons.”

Despite failing health, Bechet kept up an active schedule of performing and recording. In addition he recounted an extensive oral history to journalist Joan Reid. These interviews, and additional ones with journalists Desmond Flower and John Ciardi, were edited by the latter two into Bechet’s autobiography Treat It Gentle. Unfortunately Bechet died before the book was published.

Sidney Bechet’s music was regarded as passé for some time, much like the work of Louis Armstrong, but a deserved renaissance has brought it back to appropriate prominence. At this writing his legacy shines brightly thanks to such clarinetists as his former student Bob Wilber, and the New Orleans clarinetists Dr. Michael White, Tim Laughlin, and Evan Christopher.

——–

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based journalist, folklorist, drummer, and producer. Sandmel is the author of Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans and Zydeco!, a collaborative book with photographer Rick Olivier. Sandmel has produced and played on albums including the Grammy-nominated “Deep Water” by the Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers.

Suggested reading:

Treat It Gentle (autobiography), Sidney Bechet, DaCapo Press, 2002

Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz, John Chilton, DaCapo Press, 1996

The clarinet is a type of woodwind instrument that has a single-reed mouthpiece, a straight cylindrical tube with an approximately…