Louis Armstrong “Satchmo”

1901 – 1971

1901 – 1971

By Ben Sandmel

Trumpeter, cornetist and singer Louis Armstrong is often erroneously regarded as the sole inventor of jazz. This honorific is intrinsically impossible, because the evolution of any musical genre is a complex and gradual socio-cultural process. It is quite appropriate, however, to state that Armstrong made vital, indispensable contributions to the emergence of jazz, in New Orleans, which was one of such music’s prime points of origin. (It is similarly erroneous — although equally prevalent — to cite New Orleans as the sole “birthplace” of jazz, because other regions contributed significantly to the emergence of this multi-cultural music.) As his career progressed, on the global stage, Armstrong became one of the most important and influential musicians of the 20th century.

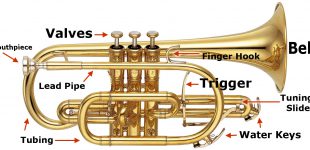

Along with Sidney Bechet, Jellyroll Morton, King Oliver, and others, Armstrong represented the second-generation of jazz artists to emerge from New Orleans circa 1915 – 1925. But the city was not receptive or supportive towards jazz in those days, and Armstrong’s estimable career unfolded outside of New Orleans. His success, popularity and high regard were based on several factors. Armstrong was a deft, imaginative instrumentalist. He started out on the cornet, an instrument that is very similar to the trumpet, and later began playing the trumpet per se. Armstrong was a major innovator in terms of making the trumpet an important vehicle for improvisation, a highly fluid approach to rhythm, and a bold experimental approach to phrasing that flirted with rhythmic disaster but never stumbled. He played with deep, expressive emotionalism, vast range and a sublimely clear tone. In addition to this instrumental prowess, Armstrong applied the same aesthetic approach to his singing, which was extremely soulful and often included the non-verbal concept known as scat singing, in which his voice functioned as an instrument. This multi-talent significantly elevated the standards of musicianship among jazz players and vocalists alike. By the 1960s Armstrong also attained renown became a pop-music icon and a personable performer, beyond the realm of jazz.

Armstrong gave his birth date as July 4, 1900, although the late scholar Tad Jones discovered the true date to be August 4, 1901. Armstrong was raised on Jane Alley in a rough neighborhood known as “back of town,” near the present location of Orleans Parish Prison, in an area known as “back of town.” In a retrospective interview with Life magazine, Armstrong recalled having “…a ball growing up there as a kid. We were poor and everything like that, but music was all around you. Music kept you rolling.”

The childhood music referred to included spirituals, military parade music, blues, and ragtime — which, when seamless combined around the turn of the century, forged the music now known as jazz. As a child Armstrong would stand outside a neighborhood bar called the Funky Butt Hall, and watch performances through chinks in the walls. He also absorbed early jazz — as first played by such artists as Charles “Buddy” Bolden – at funeral processions, second-line parades, and other community gatherings. Armstrong also held a laboring job in the New Orleans red-light district known as Storyville, where the sporting house featured some of the best musicians in town, whom Armstrong studied carefully.

As a pre-teen Armstrong began singing on the streets with other neighborhood kids; significantly, he sometimes accompanied them on a slide whistle. At age twelve Armstrong got arrested for firing a pistol in the air on New Year’s Eve. He was sent to the Colored Waifs Home, where teacher/bandleader Peter Davis taught him to play the cornet and read music. (Davis also trained the great R&B trumpeter, songwriter and bandleader, Dave Bartholomew.) Leaving this facility a year and a half later, Armstrong began performing at nights with various groups/bandleaders while still doing manual labor by day. During the next five years Armstrong’s ability, and renown increased significantly in New Orleans, and at age eighteen he was hired by Edward “Kid” Ory, to the noted trombonist, to replace Joseph “King” Oliver who had formed his own band. Oliver soon lured Armstrong away to join that group for a house-band position in Chicago. Armstrong thus attained the status of a full-time professional musician, and further solidified his reputation by recording with King Oliver’s band in 1923. As demand for Armstrong’s services increased, he was also hired to accompany recording artists ranging from country star Jimmie Rodgers to the great blues singer, Bessie Smith, whose records he considerably enhanced as a soloist. Armstrong was also in demand as a vocalist, as evidenced by his collaboration with pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines on “Rockin’ Chair.”

The Hot Fives and Hot Sevens recordings that Armstrong made as a bandleader between 1925 and 1928 are cited as ultimate examples of traditional, classic New Orleans jazz. The best known songs among this material included “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue,” “West End Blues”; and “Cornet Chop Suey,” besides Armstrong’s spirited, innovative playing there were also great performances by such prominent players as Johnny Dodds, Kid Ory, drummer Warren “Baby” Dodds, and banjoist Johnny St. Cyr.

From the late 1920s until, roughly, the end of World War II, Armstrong worked both as sideman and bandleader in formats ranging from small combos, big bands, and in orchestras for musical revues. He appeared in films, and recorded with such popular mainstream artists as Bing Crosby. He emerged as a familiar and beloved national figure and appeared in films with such popular mainstream artists/movie stars as Danny Kaye, and Bing Crosby. When the economics of the post-War era brought an end to the big band era, Armstrong adapted by downsizing as the leader of an aptly-named band called the All-Stars, whose recorded legacy includes an historic live performance from 1947 at the Town Hall in New York. Distinguished personnel in this band, included drummer Big Sid Catlett, trombonist Jack Teagarden, and clarinetist Barney Bigard.

From this point until his death in 1971 Armstrong toured and recorded continually, reaching ever-broader audiences. In 1964 his number-one record, “Hello Dolly,” which briefly eclipsed The Beatles’ dominance of the pop-charts. But Armstrong’s late career years also included some controversy. The 1960s found America in cultural and political upheaval, as manifested in jazz by the deliberately dissonant sounds of be-bop era, and the social turmoil of the Civil Rights era. In this context, Armstrong’s exuberantly smiling performance style was scorned by some observers. He was even dismissed – by politicos and musician alike, as Uncle Tom. Such criticism ignored Armstrong’s sharp political comments regarding the school desegregation crisis in Little Rock, AR, in 1957.

This perception lingered after Armstrong’s passing. But such sentiments are cyclical, and, some ten years later, Armstrong was appropriated lauded by a new generation of jazz artists, most notably Wynton Marsalis. The past three decades have seen Louis Armstrong’s oeuvre and reputation retain their richly deserved prestige.

——–

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based journalist, folklorist, drummer, and producer. Sandmel is the author of “Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans” and “Zydeco!”, a collaborative book with photographer Rick Olivier. Sandmel has produced and played on albums including the Grammy-nominated “Deep Water” by the Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers.

Suggested reading:

New Orleans Style and the Writing of American Jazz History, Bruce Boyd Raeburn, University of Michigan Press

Satchmo: My Life In New Orleans, Louis Armstrong, DaCapo Press, 1986

Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans, by Thomas Brothers, W. W. Norton, 2006

New Orleans Style and the Writing of American Jazz History, Bruce Boyd Raeburn, University of Michigan Press, 2009

Singing is the act of producing musical sounds with the voice, and augments regular speech by the use of both…

A trumpet is a musical instrument. It is the highest register in the brass family. Trumpets are among the oldest…

The cornet is a brass instrument very similar to the trumpet, distinguished by its conical bore, compact shape, and mellower…