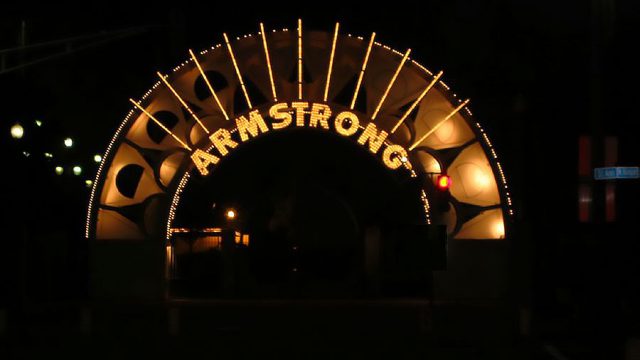

Image Credit: Christine Foley

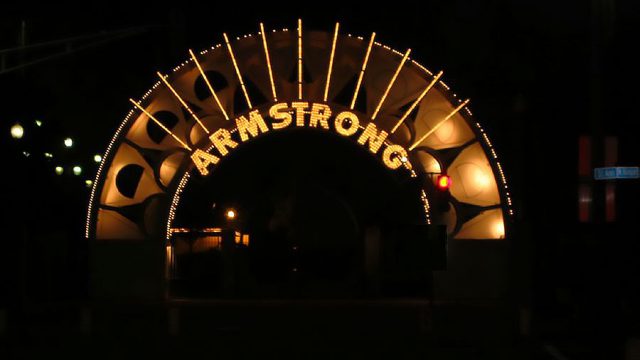

Image Credit: Christine Foley

Just steps away from the French Quarter is a 31-acre public park named after and dedicated to the “Satchel-Mouth”:http://musicrising.tulane.edu/discover/places/17/Louis-Armstrong-Park , a revolutionary jazz musician from the city of New Orleans. The park is located in the historic neighborhood of Tremé, a faubourg with deeply rooted music culture. The park, which is intended to celebrate the rich jazz history of New Orleans, honor New Orleans’ jazz prodigy, commemorate the site of Congo Square, and introduce open public space in a downtown area, has faced many trials and tribulations since its opening on April 15, 1980.

Initial Planning

[Description excerpt taken from “MediaNOLA“]

The role that Louis Armstrong played in the development of jazz, and American music in general, had a monumental affect. New Orleanians wanted to honor him with a “permanent tribute” after his passing in 1971. Under Mayor Moon Landrieu, a Citizen’s Committee formed to discuss plans for the design of a memorial for Armstrong. Planners, architects, jazz scholars, musicians, and community activists met to decide where and in what form the memorial would be implemented. Various suggestions were proposed on what the dedication could be, including bandstands, educational systems for music and the promotion of cultural arts, fountains, monuments, among other things. When plans for a Treme Cultural Center fell through, mostly because of funding issues, the 14-member Citizen’s Committee proposed that the vacant land surrounding the Municipal Auditorium be transformed into a park that would incorporate some of these elements. It was reported in a New Orleans States Item that the hope was that the park would help recreate “the spirit of ‘Milneburg and West End’ where live entertainment was once featured and New Orleanians and visitors alike found a meeting place for music, good food, entertainment, and fun.”

Preceding the Armstrong Park proposal, the site on North Rampart had been wiped out of its contents with the intention to make room for a Treme Cultural Center. The neighborhood was demolished; old bungalow cottages were torn down, along with neighborhood bars and live music venues. The demolition displaced more than 1,900 people. City officials recognized that the vacant site needed to be addressed once it was clear that the plan for the Cultural Center was not going to be completed.

The Armstrong Park proposal seemed to officials a logical resolution both financially, because the city already owned the land, and socially, stating that in its current state it was “a disaster area, serving as a depressant to the Treme community.” Mayor Landrieu felt that this site offered great potential as the Times-Picayune reported his statement, “the value of open space in the downtown area as an enhancement to developers, shoppers, visitors and workers is unquestioned. We cannot afford to miss this opportunity to acquire and develop open space downtown.” Once the site was decided upon, the Louis Armstrong Memorial Committee, with the New Orleans City Planning Commission, commissioned the design of the park to San Francisco-based urban design firm Lawrence Halprin & Associates.

While Lawrence Halprin & Associates prepared a plan for the park, controversy sparked among interest groups who were both for and opposed to the park’s implementation. Frequent theater goers protested the plan, arguing that a memorial should not be placed in the vicinity of the Municipal Auditorium, as it would detract from the performing arts and create parking problems. Other dissenters felt that overall the deign would “create a Disneyfied New Orleans, providing artificial entertainment for profit when the city has plenty of authentic attractions outside the park.” Those in favor of the park had opposing ideas on how exactly it should be structured. On one side, political agendas leaned towards appealing to tourism to spur economic growth, and therefore favored designs that made it attractive to outsiders. These ideas included things such as a Ferris wheel and other carnival type attractions. On the other hand, Tremé community leaders felt a tribute park to Louis Armstrong “with facilities to educate and enrich the lives of the residents of the city” would better serve the community.

Despite the opposition, the creation of Armstrong Park was approved by the City Council. Officials made adjustments to the planning structure in order to settle some of the controversy. Lawrence Halprin & Associates were removed from the project, and New Orleans architect Robin Riley, who had been working closely with the firm, was given the lead on the project. The amusement park components were taken out and parking spaces were added to the plan. Mayor Landrieu adjusted the budget in order to build a parking garage to relieve parking requirements for the Municipal Auditorium and Theater for Performing Arts. The opening of the Louis Armstrong Park was celebrated by the city with a festival of live music, food, Mardi Gras Indians, and local vendors on April 15, 1980. The park operated daily from 9 am to 10 pm from its opening.

The design was carefully planned to beautify the area. The lighted gateway entrance honoring the name “Armstrong” leads into meandering paths, grassy knolls, lagoons, a statue of Louis Armstrong, as well as other pieces of art. The entire park is surrounded by a fence which acts as a boundary for important sites within the site. The design pays homage to Congo Square, a space where slaves in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were permitted to gather on Sundays to play their music. The Municipal Auditorium, Mahalia Jackson Center for the Performing Arts, and Perseverance Hall also occupy the park. State council members hoped that the park’s design and location would serve the “leisure-time needs of the adjacent French Quarter and Tremé neighborhoods and the day-time population of the Central Business District.”

City officials became aware of the major flaws that existed in the planning of the park when a Special Task Force prepared a detailed report for Mayor Ernest Morial that outlined its overarching problems. The report detailed park conditions which pointed mainly to negative circumstances and found that the issues rested in the “lack of official oversight, the absence of a use plan, uncertainty concerning future management personnel, parking, funding, its relationship to other attractions, and its relationship with the Tremé Community Center.” Users grew skeptical of the park’s condition as rumors began milling about the park becoming privatized, which would result in a fee to enter the park and restrict accessibility to many Tremé community members. Maintenance also lacked, as patrons saw, “trash containers overflow, and large hills over-grown with weeds.” In addition, instances of muggings and violence in the area resulted in the site becoming synonymous with crime and fear. The reputation quickly escalated when a woman from Ohio was shot and killed in an attempted burglary attack while she was walking around the park taking pictures on a weekday morning.

Mayor Sidney Barthelemy recognized that action needed to be taken in the park to fix these problems, and in 1987 he stated he wanted to “end the inactivity that has made the park a source of controversy since it opened.” Bathelemy pioneered a committee to resolve the issues of Armstrong Park. The committee decided to involve the Tivoli Corporation to transform the site into a version of Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, complete with gardens, live entertainment, shops, restaurants, and rides, making it a “cultural amusement park.” The mayor and committee members met with Copenhagen officials and designers of the original Tivoli project, and attempts were made to push the proposal through. The park would require an admission fee, and major physical design changes would be made. Though it was promised that the design would promote distinct New Orleans culture, community members feared the project would “highlight European rather than black culture.”

A Citizen Committee was assembled to study the design proposals, which resulted in outright rejection due to the necessary entrance fees and clashing design ideas that were “outside of the cultural and architectural context of the neighborhood.” By the early 1990s, the project received such strong opposition from the Treme community and was unable to receive adequate support and funding that the plan was terminated. After these efforts fell through, few attempts were made by city planners to revamp the park, though the conditions remained status-quo. Then, in 2005 with devastation of Hurricane Katrina, all efforts ceased and Armstrong Park remained closed until 2011.

When Mayor Mitch Landrieu took office in 2010, he decided, along with the New Orleans City Council, to make the revitalization of Armstrong Park a priority. Prior to Mitch Landrieu’s administration, construction efforts for the park were handled with haste and poor execution. Landrieu felt that Louis Armstrong Park was “one of our City’s greatest cultural and historic treasures,” and therefore decided to concentrate efforts on beautifying the park. Five years after Hurricane Katrina on November 18, 2011, all phases of renovation were completed and the Armstrong Park was opened to the public. Today the park operates from 8 am to 6 pm daily, and public relations and event planning components are beginning to take shape. The weekly live music events of “Jazz in the Park” is offered throughout the summer into early fall, as well as an annual Tremé Creole Gumbo Festival.

Works Cited

1. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

2. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

3. Allan Katz. “Satchmo Tribute Asked.” New Orleans States Item. 30 June 1972.

4. Kathleen Frick. “Watchful Neighborhood Surrounds Armstrong Park.” Times-Picayune. 17 August 1980.

5. City of New Orleans Public Relations Office, Press Release, 30 June 1972, New Orleans City Archives.

6. “Mayor Submits Budget to N.O. City Council.” Times-Picayune. 29 October 1972.

7. “Howard Jacobs. “News of the Week in Review.” Times-Picayune. 7 July 7.

8. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

9. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

10. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

11. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

12. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

13. “Mayor Submits Budget to N.O. City Council.” Times-Picayune. 29 October 1972.

14. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

15. Allan Katz. “Satchmo Tribute Asked.” New Orleans States Item. 30 June 1972.

16. Allan Katz. “Satchmo Tribute Asked.” New Orleans States Item. 30 June 1972.

17. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

18. Kathleen Frick. “Watchful Neighborhood Surrounds Armstrong Park.” Times-Picayune. 17 August 1980.

19. AP. “Suit Filed in Death.” The Advocate (Baton Rouge). 31 December 1987.

20. AP. “Suit Filed in Death.” The Advocate (Baton Rouge). 31 December 1987.

21. AP. “‘Gentlemen’s Agreement'” reached on NO Park.” The Advocate (Baton Rouge). 9 September 1987.

22. Coleman Warner. “Loan OK’d to revamp Armstrong.” Times-Picayune. 19 October 1990.

23. Michael E. Crutcher Jr. “A Park for Louis.” in Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

24. “Mayor Landrieu and the New Orleans City Council with City Officials Re-Open Historic Armstrong Park.” New Orleans City Council. 18 November 2011. http://nolacitycouncil.com/.

25. Editorial Staff. “Finishing Louis Armstrong Park in New Orleans.” Times-Picayune. 6 October 2010.

26. “Mayor Landrieu and the New Orleans City Council with City Officials Re-Open Historic Armstrong Park.” New Orleans City Council. 18 November 2011. http://nolacitycouncil.com/

27. “Mayor Landrieu and the New Orleans City Council with City Officials Re-Open Historic Armstrong Park.” New Orleans City Council. 18 November 2011. http://nolacitycouncil.com/

28. “Jazz in the Park: Treme Music Series.” People United for Armstrong Park. May 24, 2012. http://www.pufap.org/jazz-in-the-park-treme-music-series/