Charles “Buddy” Bolden

1877 – 1931

1877 – 1931

By Ben Sandmel

The first documented practitioner of the music now known as New Orleans jazz was cornetist Charles “Buddy” Bolden (1877-1931). Legend has it that Bolden’s playing could be heard for miles around town when he would “call [his] children home.” Such anecdotes, combined with a relative dearth of solid information, combined to make Bolden a mythic figure. His musical innovations and tragic life story have inspired fictional works including David Fulmer’s Chasing The Devil’s Tail, and Coming Through Slaughter by Michael Ondaatje. On a more immediate level Bolden inspired such early jazz songs as Sidney Bechet’s “Buddy Bolden Stomp,” and “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say” (a.k.a. “Buddy Bolden Blues”) by Jelly Roll Morton.

Bolden performed from 1895 to 1906. No interviews with him are known to exist. Allegedly, he made a few recordings, but these are thought to have been carelessly thrown away as trash. The most significant extant artifact is a photo of Bolden and his band that was taken in 1905. In addition to Bolden on cornet, the group included a trombonist, an acoustic guitarist, an acoustic bassist, and two clarinetists. A certain degree of controversy surrounds the photo because some observers claim that it was printed backwards.

As is often the case with pioneering musicians, Bolden’s important contributions to what would come to be known as jazz were not appropriately appreciated during his lifetime. It was not until the 1930s – when jazz was first regarded as a genre of substance that merited historic documentation – that researchers began to examine Bolden’s life and career. While hard facts were difficult to find, Bolden’s name was still prominent in oral history and collective memory. Accordingly the early jazz scholars who researched Bolden story relied on interviewed his surviving band members and associates. Some of these people had self-serving egotistical agendas, while others’ memories were imprecise. The information they imparted was not always accurate or objective, but it nonetheless came to be accepted as fact and was widely disseminated as such. In the 1970s, Donald M. Marquis, then the jazz curator of the Louisiana State Museum, undertook an in-depth study that separated fiction from fact. The result was Marquis’ book definitive book In Search of Buddy Bolden: First Man of Jazz.

The son of Westmore Bolden and Alice Harris, Charles Bolden was raised in New Orleans in the neighborhoods now known as Central City, and the Irish Channel. He learned the rudiments of the cornet from a neighbor named Manuel Hall. Bolden was also influenced by the wealth of music he heard being performed in New Orleans. These sounds included spirituals, jubilee singing, and the exuberant “shouts” from his Baptist background. The brass bands that played at a wide range of both religious and secular functions also shaped Bolden’s musical style. These bands performed a blend of ragtime and military music that synthesized African and European concepts, presaging the hybrid that soon became jazz.

In addition, it seems logical to assume, despite a lack of solid evidence, that Bolden absorbed various then-current African-American and Afro-Caribbean folk traditions of the day. The blues form, though dating backing to antebellum music, came to be known by this name and came to be increasingly popular and standardized during Bolden’s childhood. In addition, performances by groups that played utilitarian items that doubled as instruments – such as jugs, washboards, and the washtub bass – presaged the jazz practices of improvisation and the use of stop-time. And archaic song forms such as ring shouts, work songs, and field hollers still resonated throughout the South at this time. In New Orleans this aesthetic also included a tradition of singing street vendors that flourished for generations, up until Hurricane Katrina.

It’s also likely, although undocumented, that Bolden felt the influence of the African-retentive vocal chants and Afro-Caribbean drumming that had thrived in the New in New Orleans during the first half of the nineteenth century, most notably at weekly slave gatherings at Congo Square. Aspects of this tradition – especially its aesthetics of polyrhythm, syncopation, and improvisation – lingered long in the city, and, while significantly modified by the passing of time, they remain palpable and important today. Bolden would also have heard African American and Creole musicians playing more standardized European forms such as the waltz, quadrille, schottische, and mazurka, as well as military marches.

A guitarist named Charles Galloway initially formed the band that Bolden played in, around 1895. Bolden soon became the leader, however, reflecting his reportedly extroverted personality and the loud, aggressive cornet playing style that many observers noted. Initially working by day as a laborer, Bolden became a full-time musician as the band’s popularity grew. By 1902 he was listed as a musician in the New Orleans city directory. As the band’s following expanded, Bolden acquired the nickname “Kid,” which designated an up-and-comer. When “King replaced this moniker” it meant that Bolden had reached the peak of his profession. In great demand, Bolden and his band performed constantly, playing both dances and parades, all over town. He concentrated, however, on the strip of clubs and taverns around the intersection of South Rampart and Perdido Streets, which was known as Back-of-Town.

Many prominent early New Orleans jazz musicians played and/or associated with Bolden. These included clarinetists George Baquet, Alphonse Picou, and a young Sidney Bechet; bassist Alcide “Slow Drag” Pavageau; multi-instrumentalist Peter Bocage; cornetist/alto saxophonist Isidore Barbarin; and drummer Louis Cottrell. Bolden’s main competitor as a soloist was the violinist who headlined John Robichaux’s Dance Orchestra.

By 1906, Bolden had suffered several psychotic episodes that included an assault on his mother. This mental problem – plus the pressures of performing and the deleterious effects of alcohol – ended Bolden’s career. After several arrests, he was declared insane. In 1907 Bolden was committed to a state mental hospital in Jackson, Louisiana. He was diagnosed with dementia praecox, now known as schizophrenia. These circumstances spawned the bizarre theory, proposed in 2001 by Dr. Sean Spence of the University of Sheffield, U.K., that Bolden’s musical talent constituted a clear symptom of his mental illness. By extension, Spence ludicrously implied, jazz is a psychiatric condition.

Bolden spent 24 years at Jackson until his death in there 1931. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the Holt Cemetery in New Orleans’ Mid-City section. Ninety years following his mental breakdown, Bolden was honored with a second-line funeral and the installation of a monument at this cemetery.

———

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based journalist, folklorist, drummer, and producer. Sandmel is the author of “Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans” and “Zydeco!”, a collaborative book with photographer Rick Olivier. Sandmel has produced and played on albums including the Grammy-nominated “Deep Water” by the Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers.

Suggested Reading

Ashforth, Alden. “The Bolden Band Photo—One More Time.” Annual Review of Jazz Studies 3 (1985): 171–80.

Barker, Danny, and Alyn Shipton. Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2001.

Carney, C. “New Orleans and the Creation of Early Jazz.” Popular Music and Society 29 no. 3 (July 2006): 299–315.

Marquis, Donald M. In Search of Buddy Bolden: First Man of Jazz. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Suggested Links

“Calling His Children Home.” New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park. National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/archive/jazz/Jazz%20History_buddy_bolden.htm

“Mental illness ‘at the root of jazz.’” BBC Homepage. British Broadcasting Corporation. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/1430337.stm

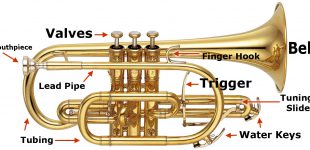

The cornet is a brass instrument very similar to the trumpet, distinguished by its conical bore, compact shape, and mellower…